Matarajin was a deity that was widely worshipped in medieval Japan but, in modern times, fell off the radar. He is represented in many forms and serves many purposes, with both of these aspects being confused and changing over time. He is a god of obstacles who was brought by Ennin (圓仁 or 円仁) in a return trip from China.

Appearance

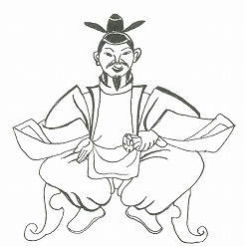

In his most well known form, he is an old man wearing the typical clothes of an aristocrat and carrying a small drum (tsudzumi 鼓), with the company of his two youthful attendants, Chōreita Dōji (丁令多童子) and Nishita Dōji (爾子多童子). All of them are under the watch of the Big Dipper.

In his earliest forms, he is a three-faced Yakṣa (a type of ogre in Buddhism) god. He assumed more of a female form.

Roles

Matarajin is associated with many things, often contradictory and paradoxical.

In his Yakṣa god form, he is the protector of Tō-ji (東寺), a Shingon Buddhist temple in Kyoto, with the role of subduing ghosts and demons. He is also referred to as another form of Mahākāla, and at the same time a bloodthirsty ḍākinī or a matrika. The association with the Seven Mothers might have developped his link to the Big Dipper.

He is one of the protector deities, with Sannō (山王) and Tōshō (東照), of the Nikkō Tōshō-gū (東照宮) shrine, guarding the Tokugawa government and ensuring its properity. During the Shushō-e New Year ritual, seven masks symbolizing the Big Dipper escort Matarajin's dharma body.

In Tendai, in the exoteric practice, he came to be seen as the protector god of Nembutsu and the Jōgyōdō hall in many Tendai temples throughout Japan. The reason for it being the Jōgyōdō hall is because one of the practices, Jōgyō Zanmai, is walking around Amida (Amithaba) for 90 days while reciting Nembutsu. He is enshrined close to the Jōgyōdō on Mount Hiei, with the implication that he descends as a mountain god.

Another more esoteric interepretation is that he is a wrathful manifestation of Amida, cutting the breath at the time of death to better lead to rebirth and eating the liver so that the person develops correct thoughts leading to rebirth.More on his demonic aspects, Matarajin is worshipped at the back door, the Demon Gate, alluding to his powers of protecting from demons and probably his past as a demon of obstacles. However, there is little evidence of this. Furthermore, in an esoteric ritual called Tengu Odoshi (天狗怖し), where tengu were subdued by feigning frantic behaviour as typical placating rituals didn't work on them, his role is scaring tengu away, a manifestation where he is a tengu or a demon king.

There is also his role in the Genshi Kimyo-dan (玄旨帰命壇) esoteric ritual. It is argued whether the honzon (main object of worship) is Matarajin or the Big Dipper, associating Matarajin with destiny and the stars. A dance is practiced while saying "shishirishi ni shishiri" and "sosoroso ni sosoro". It is interpreted in many ways, such as bringing deliverance when performed with a pure mind but the opposite if the mind isn't. Matarajin and his two acolytes might also represent the Three Paths (defilments, karma and suffering) and the Three Poisons (greed, hatred and desire), while the dance represents our endless wandering in Saṃsāra and the beating of the drum the identity between defilements and awakening. However, the teachings of Genshi Kimyo-dan were targeted as "Heretical Teachings" and their practice became prohibited, as Matarajin's dance was seen as indencent and erotic in nature. This contributed to the downfall of the popularity of Matarajin.

He is also identified as a dream king, beating the golden drum in the Golden Light Sūtra, and in Tiantai dream cultivation techniques, providing supernatural visions for the attainment of Samādhi and insight.

Yet another role of Matarajin is during the Ox Festival (Ushi Matsuri 牛祭) in Kōryū-ji (広隆寺), another Shingon temple in Kyoto. A priest wearing the mask of Matarajin rides a black ox while he is flanked by four monks disguised as demons possibly representing the Four Heavenly Kings (四天王) or the Four Māras, while reciting a saimon designed to eliminate calamities and bring happiness and peace. This is another negative depiction where he is a demon. As a note, this festival is currently suspended.

Matarajin is also associated with Noh theater, in a way that he obstructs Buddhist ceremonies until appeased by dramatic performance, which then tranforms him into the protector of dramatic arts. He later became associated with the Okina (翁) old man mask in Noh, which plays use at the beginning with a nonsensical song.

Conclusion

Is Matarajin a god or demon of obstacles brought from China? A Yakṣa god? A manifestation of Mahākāla or Amida? A ḍākinī, or a matrika? A protector god? A dream king? This seemingly paradoxical and confusing miriad of interpretations and manifestations, further impeded by persecution, doomed Matarajin to be a relic of medieval times. However, there is a lot to observe in terms of the transformation of deities over time and traditions, esoteric inversions, and the understanding of the political and religious landscape of medieval Japan. It has certainly been confusing, yet fun to research. I have omitted quite a lot of information for brevity and simply because I did not feel confident in my understanding, so I implore you to research on your own.

Have an excellent day.

06/10/24

Addendum (12/01/25)

It seems that I have missed an important and still practiced festival in Mōtsū-ji (毛越寺), Iwate prefecture, the Mōtsū-ji Hatsukayasai Festival. I'll just quote the source: "The Matarajin Festival is held at the Jōgyōdō Circumambulation Hall from January 14 to 20 to celebrate the New Year. The final night, January 20, is particularly auspicious for prayer. Several rituals are performed, including the ancient rite of samadhi by constant walking. Additionally, a torchlit parade of worshippers of all ages makes its way to the Jōgyōdō Hall, where offerings including daikon and napa cabbage are made to pray for household safety and protection from disease and disaster.The night ends with a performance of the Ennen no Mai longevity rites."And another: In addition to the principle image of Amitabha Nyorai, Matarajin (rarely shown to the public), who is considered to be the guardian deity of Mōtsū-ji, is also enshrined here. The Hatsukayasai Festival held each January 20 to pray to Matarajin. After the monks give prayer and austerities during “Jōgyō Zanmaiku,” “Ennen” (Longevity) is presented.